I was born in Moscow, then USSR, in 1984, to a Ukrainian father and a Russian mother. Currently I am based in Paris.

A journalist by education, I picked up photography in search of means of expression alternative to words in the absence of freedom of expression in Russia I already felt in early 2000s. Filmmaking came naturally after that, a love from the first sight. I decided not to choose between the three mediums and combine them all for the benefit of telling complex stories on human rights, religion and conflict.

Selected exhibitions

2022 This World That Watches Us: 15 Years of NOOR, group show, French National Library, Paris

2020 Abkhazia and South Ossetia: Lost and Found, Open Gallery, Bratislava, Slovakia

2020 I exist: European stories of Islamophobia, group show by NOOR, Melkweg, Amsterdam, Netherlands

2018 Grozny: Nine Cities, Les Rencontres de la photographie, Arles, France

2015 Grozny: Nine Cities, Visual Culture Research Center, Kiev, Ukraine

2014 Grozny: Nine Cities, Le Radar, Bayeux, France

2014 Grozny: Nine Cities, National Gallery, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina

2013 Grozny: Nine Cities, STATION-Berlin, Berlin, Germany

2012 Grozny: Nine Cities, Palau de la Virreina, Barcelona, Spain

Selected Awards and Grants

2021 Brouillon d’Un Rêve film development grant by the French civil society of multimedia authors

2017 Winner, Luma Rencontres DUMMY BOOK AWARD Arles 2017

2017 Best DEBUT Film award, It’s Getting Dark, DocuTIFF film festival, Tirana, Albania

2015 Great Lakes Reporting Fellowship, International Women Media Foundation

2014 Journalists on Location grant, Robert Bosch Stiftung

2014 Prix Bayeux-Calvados for War Correspondents

2012 PDN Photo Annual prize

2012 Magnum Emergency Foundation grant

2011 Lens Culture International Exposure Award

2010 Chevening Scholarship

2009 Rory Peck Trust bursary

Collections

French National Library

Les Rencontres d’Arles

The Open Society Foundation

Private collections in France and Russia

Film festivals

IDFA 2016 (Amsterdam, Netherlands)

Artdocfest 2016 (Moscow, Russia)

Zargebdox 2017 (Zargeb, Croatia)

Tempo 2017 (Stockholm, Sweden)

DocuTIFF 2017 (Tirana, Albania)

Cinéma Vérité 2017 (Tehran, Iran)

In 2016, I directed my debut documentary, It’s Getting Dark – the story of five families of political prisoners across Russia through time, premiered at the prestigious IDFA festival in Amsterdam, Netherlands. I worked with the question of historic memory in Russia, inspired by a former Gulag prisoner who told me that she saw history repeating itself in modern Russia while citizens were turning a blind eye to it.

In 2018, together with fellow authors Oksana Yushko and Maria Morina and curator Anna Shpakova we completed a crossmedia project that took almost a decade in the making, Grozny: Nine Cities. We combined investigative journalism, documentary photography, video and archives to produce a three-screen installation for museums, a web-documentary in open access for web, and a book to tell the story of the aftermath of two wars Russia waged in Chechnya. The project was published, awarded and exhibited internationally, including at Rencontres d’Arles, France, the most important photography festival in Europe, and in Kyiv, Ukraine following the Russian annexation of Crimea.

In 2022, I published my second book, More Fear Than Allah, on persecution of Russian converts to Islam by security services, in which I break away from journalism and embrace engaged authorship.

Clients I worked with

Press about me

Aesthetica Magazine

The Next Generation: Olga Kravets

In the Special 60th Edition of Aesthetica we celebrate the emerging photographers that are shaping the future of the image-based practice in The Next Generation. We have partnered with the London College of Communication to survey some of photography’s rising stars and showcase their fresh ideas and new concepts. Russian born documentary photographer Olga Kravets began her career as as a journalist in 2002 and became a freelance photojournalist in 2007. Her striking images are often captured within conflict zones and she discusses the dangers of capturing these shots and the impact it has on her.

A: In Aesthetica Issue 60 your image of Russian soldiers appears in The Next Generation feature. Can you explain the story behind this photograph?

OK: The image was taken shortly after four suicide bombers detonated their explosives, killing three other people on October 19, 2010, next to the parliament building in Grozny, Chechnya. The soldiers stood guard for hours, but there was nobody to fight. Then, very quickly, cleaning ladies came and washed away the blood from the stairs of the building and Chechnya’s leader Ramzan Kadyrov proudly led the Russian Interior Minister, “who happened to be around”, in, to give a speech about the fight against terrorism.

A: The image was taken in an area of conflict, is this something you are interested in, in your practice?

OK: I wouldn’t say I am interested in conflict, I hate every notion of conflict, but unfortunately, as long as violence exists it needs to be reported. If it was up to me, I would like to see all unrest undone. My Chechnya image is an example of a forgotten story and I would say I specialise on the stories nobody wants to cover, that’s why normally you don’t find me in the press crowds.

A: This work is a documentary shot, do you work in any other type of photography?

OK: I am about to do my first ever commercial job later this year, but it will carry elements of documentary because I was selected for my pure attachment to one genre. But, I also want to do a big studio project about torture, to recreate something I was told about, but would never be able to photograph in real life – I still need funding for it.

A: Areas of conflict are obviously very dangerous places for photographers to work, does this concern you? What draws you to these places?

OK: What really concerns me is the lack of responsibility the media is willing to carry for their photographers and reporters in those places. When Syria was just starting, I was in the office of one of the big editors and I told him I would go if there is an assignment, which means travel and fixer expenses, insurance and flack jacket. He said I should call him if “I find myself” in Syria. That’s the issue – the reason there is such a massive mortality rate among young journalists is because they are encouraged to “find themselves” in war zones and just hope that somebody buys the pictures. The more people do it, the more normal it will become and more people will die on their first trips. For my first trip I was drawn by curiosity but once you meet a mother, whose son was taken from the house in the night by some masked men and will never come back, or see a man who survived torture collapse of a stroke, you can’t ignore the injustice in the world. It takes a great deal of self-control not to feel guilty, for instance, while enjoying my vacations.

A: What do you have planned for next?

OK: I am working on a full length documentary film, nothing to do with still photography this time. Working a lot with multimedia actually made me wanna try the real cinema and I’ve been lucky enough to have meet a great producer who believed in me – we are starting to film in September.

See Olga Kravets’ photography in The Next Generation in the Special 60th Edition of Aesthetica. Pick up a copy at www.aestheticamagazine.com

(FR) Rencontres d’Arles : coup de flash sur les profondeurs de Grozny

Rencontres d’Arles : coup de flash sur les profondeurs de Grozny

Trois jeunes photographes russes exposent leur remarquable travail sur la capitale tchétchène.

Sur des cartes postales ensoleillées, au bord de la rivière Sounja, quelques promeneurs longent d’élégants bâtiments. Cette première vision de la capitale de la Tchétchénie au temps de l’époque soviétique, qui ouvre l’exposition « Grozny, neuf villes » aux Rencontres d’Arles, au premier étage du Monoprix, semble irréelle. Quelques pas plus loin, des photos de ruines épouvantables les remplacent, rappelant que pour l’ONU, en 2003, Grozny était « la ville la plus détruite du monde ». Satsita Israilova, la bibliothécaire de Grozny, qui pendant les deux guerres de Tchétchénie (1994-1996 et 1999-2000) s’est employée à sauver autant les livres que les gens, a collectionné ces images, prêtées pour l’exposition. Elle-même a pris des photos, en particulier des arbres abîmés par les bombes, parce que « ces plantes étaient à l’image de [s]on âme »

Aujourd’hui, le centre de la ville a encore une fois complètement changé: rasé, il a été reconstruit avec des buildings arrogants. Mais le poids du conflit, pourtant officiellement terminé, pèse toujours sur les habitants. Et sur la Russie entière: c’est parce que la Tchétchénie est aujourd’hui, selon elles, « le point le plus douloureux sur la carte » que trois jeunes photographes russes, Oksana Yushko, Maria Morina et Olga Kravets ont passé près de neuf ans à enquêter, récolter des documents et photographier les lieux. « La guerre de Tchétchénie a marqué toute une génération, explique Olga Kravets, parfaitement francophone, à travers les jeunes qui ont été soldats là-bas pendant leur service militaire obligatoire. C’est comme un cancer dont on ne parle pas »

Aujourd’hui, le centre de la ville a encore une fois complètement changé: rasé, il a été reconstruit avec des buildings arrogants. Mais le poids du conflit, pourtant officiellement terminé, pèse toujours sur les habitants. Et sur la Russie entière: c’est parce que la Tchétchénie est aujourd’hui, selon elles, « le point le plus douloureux sur la carte » que trois jeunes photographes russes, Oksana Yushko, Maria Morina et Olga Kravets ont passé près de neuf ans à enquêter, récolter des documents et photographier les lieux. « La guerre de Tchétchénie a marqué toute une génération, explique Olga Kravets, parfaitement francophone, à travers les jeunes qui ont été soldats là-bas pendant leur service militaire obligatoire. C’est comme un cancer dont on ne parle pas »Convaincues qu’ « il y avait autre chose là-bas que ce qu’en montre la télévision russe », les trois jeunes femmes ont mené un travail de long terme qui a d’abord pris la forme d’un webdocumentaire primé au festival de Bayeux en 2014. Le prix de la maquette de livres, remporté aux Rencontres d’Arles en 2017, a enfin permis à un ouvrage de voir le jour aux éditions Filigranes.

On oublie vite la traduction parfois approximative devant les photos poignantes, le travail documentaire poussé. Et l’approche originale: inspirées par le roman Theophilus North, de l’Américain Thornton Wilder (1973, traduit en français sous le titre de Mr. North), les trois auteures ont choisi de découper leur travail en neuf chapitres: la cité des hommes, la cité des serviteurs, la cité de la guerre… Un pour chacune des « neuf villes » qui se cachent sous la vitrine officielle qu’est devenue la capitale tchétchène depuis sa reprise en main par le président Ramzan Kadyrov. A chaque strate, la plongée est plus profonde dans une terre d’arbitraire, où la religion, les traditions et la politique semblent s’être unies pour fermer l’horizon des habitants. « C’est un peu comme passer par les cercles de l’enfer de Dante », sourit Olga Kravets. L’effet est d’autant plus saisissant qu’à chaque fois ce sont les Tchétchènes eux-mêmes qui racontent leur vie, avec leurs mots.

Le poids de la tradition

Dans le chapitre « la cité des hommes », les Tchétchènes de sexe masculin, croisés la nuit dans la rue ou dans les bars, ressemblent à des gros durs obsédés par la frime, les courses de voitures et le maniement des armes. Mais le témoignage de l’un d’entre eux jette une autre lumière sur leur destin. La guerre a privé toute sa génération d’éducation et l’a laissée traumatisée. « A l’âge de 17 ans, j’ai dû ramasser des petits bouts de chair humaine, dit-il.(…) De quelle enfance peut-on parler après ça? » Le poids de la tradition pèse sur les aînés, responsables de toute la famille. Les cadets ont le devoir d’habiter toute leur vie chez leurs parents. Et tous les hommes, pour être « respectés », se privent de toute marque de tendresse envers leurs enfants.

Les femmes tchétchènes, qui ont accepté de parler aux photographes uniquement parce qu’elles sont de leur sexe, ont un sort pire. Soumises à leur frère, leur père, leur mari, entièrement dévouées à leur famille, elles n’ont ni amies au-delà du temps de leurs études, ni même de vie sociale de couple. La moindre atteinte à « l’honneur » par une fille se règle au sein même de sa famille, discrètement – un « accident » est vite arrivé… Oksana Yushko, Maria Morina et Olga Kravets ont passé du temps à photographier les fêtes de mariage : parce que c’est le seul horizon des femmes tchétchènes. Mais aussi le seul moment où les deux sexes se croisent et échangent à distance : dans la lezginka, danse photographiée de façon quasi cinématographique, chaque geste est codé. Les images que les trois Russes livrent de Grozny dans « la cité des serviteurs » montrent une capitale couverte de portraits du président Kadyrov, rallié à Vladimir Poutine. Effaçant d’un coup de baguette magique sa lutte armée passée contre les Russes, le dirigeant a réécrit l’histoire et changé les fêtes nationales. Son régime autoritaire emprunte au régime soviétique avec son décorum, son culte de la personnalité mais aussi sa répression féroce – de peur d’avoir des ennuis, chaque habitant ponctue ses critiques de « si Kadyrov savait, il ferait quelque chose…» Les actes de contrition publique, qui rappellent les procès staliniens, se passent désormais sur YouTube. Le président s’inspire aussi d’un idéal islamique fantasmé, qu’il mélange aux traditions tchétchènes conservatrices – l’alcool est interdit, et les divorcés sont forcés de se «réconcilier».

Les femmes tchétchènes, qui ont accepté de parler aux photographes uniquement parce qu’elles sont de leur sexe, ont un sort pire. Soumises à leur frère, leur père, leur mari, entièrement dévouées à leur famille, elles n’ont ni amies au-delà du temps de leurs études, ni même de vie sociale de couple. La moindre atteinte à « l’honneur » par une fille se règle au sein même de sa famille, discrètement – un « accident » est vite arrivé… Oksana Yushko, Maria Morina et Olga Kravets ont passé du temps à photographier les fêtes de mariage : parce que c’est le seul horizon des femmes tchétchènes. Mais aussi le seul moment où les deux sexes se croisent et échangent à distance : dans la lezginka, danse photographiée de façon quasi cinématographique, chaque geste est codé. Les images que les trois Russes livrent de Grozny dans « la cité des serviteurs » montrent une capitale couverte de portraits du président Kadyrov, rallié à Vladimir Poutine. Effaçant d’un coup de baguette magique sa lutte armée passée contre les Russes, le dirigeant a réécrit l’histoire et changé les fêtes nationales. Son régime autoritaire emprunte au régime soviétique avec son décorum, son culte de la personnalité mais aussi sa répression féroce – de peur d’avoir des ennuis, chaque habitant ponctue ses critiques de « si Kadyrov savait, il ferait quelque chose…» Les actes de contrition publique, qui rappellent les procès staliniens, se passent désormais sur YouTube. Le président s’inspire aussi d’un idéal islamique fantasmé, qu’il mélange aux traditions tchétchènes conservatrices – l’alcool est interdit, et les divorcés sont forcés de se «réconcilier».Les images les plus sombres sont à la fin de l’exposition, dans la partie « la cité de la guerre », qui dévoile une ville toujours minée par la violence. Celle des guerres passées, désormais devenues taboues, avec l’arrêt de toute recherche officielle sur le nombre de disparus et de morts. Celle du régime contre tous les « traîtres », de façon brutale et souvent aveugle : sont tour à tour visés les consommateurs d’alcool ou de drogue, les femmes qui ne portent pas le foulard, les sympathisants de l’Etat islamique en Syrie, les homosexuels, ou tout opposant au régime, réel ou supposé. Les trois photographes sont allées au-delà de la Tchétchénie, en Biélorussie et en Pologne, sur la piste des centaines de Tchétchènes qui tentent chaque jour de fuir vers l’Europe. La plupart se font refouler par les gardes frontaliers polonais qui refusent d’enregistrer leur demande d’asile, au mépris des lois de l’Union européenne, et demeurent sur place, tentant désespérément chaque jour leur chance.

Les trois auteures ont, dès le départ, eu une posture originale – elles signent collectivement les images. « Cette démarche nous a semblé naturelle. On a voulu que ce soit l’histoire qui parle, pas l’ego d’un photographe. Et ces trois regards nous ont permis une approche plus cinématographique ; en fait, on a travaillé comme une équipe de tournage. » Leur trio les a aussi rendues plus fortes face aux difficultés et aux risques inhérents à un sujet aussi sensible. « Nous avons eu des problèmes, note Olga Kravets, mais c’était plus facile pour nous, qui étions trois jeunes femmes pas connues, de passer inaperçues dans cette société très masculine, que pour des reporters très identifiés. » Les trois photographes, qui ont depuis pris des voies différentes, savaient depuis le début que leur portrait sombre n’avait aucune chance d’être montré en Tchétchénie ni en Russie. « Mais on se dit que face à l’histoire réécrite par Kadyrov, ce témoignage restera, quelque part. »

Par Claire Guillot (Arles, envoyée spéciale), LE MONDE

The New York Times

The Fog Named Mladic Is Finally Caught

Many pursuers have been on Ratko Mladic‘s trail over the 15 years leading to his capture in Serbia. Few, if any, have created as chillingly eloquent a journal as the young Russian photographer Olga Kravets.

In 2010, having moved to Bosnia to join her boyfriend, Ms. Kravets set out to create a photographic representation of Mr. Mladic in absentia, showing through physical vestiges — many of them ravaged and ruined — “his past, his sordid history and his grotesque legacy, but also his enduring, immutable and iconic status within the Serbian nationalist old guard.”

She titled the work “Uhvatio Maglu” or “Catch a Fog.”

Ms. Kravets was born in Moscow and began working as a journalist in 2002. “Very soon, I realized that photography gave me a broader way to express myself not only as a journalist, but also as an artist and a human being,” she said in her Web autobiography. She studied in a photography school run by the newspaper Izvestia and became a freelance photographer in 2007.

“When I read the book ‘Quest for Radovan Karadzic,ʼ by Nick Hawton, I decided that I needed to do the story on Ratko Mladic,” Ms. Kravets told Lens in an e-mail Thursday.

I had the feeling that this issue would be somehow resolved. Even without capturing Mladic, sooner or later he would have been announced dead.

We traveled miles and miles with my fixer Milorad, who knew the places that nobody else did, due to his connections. But sometimes it felt frustrating, especially when the conflict in Libya started and I was thinking that I am still trying to “catch fog” while others were doing something important and probably would not even see the story in what I was trying to do.

But deep inside, I knew that was not the right thought. I could not imagine, though, that Mladic would be caught a month after I finished the project.

He was. And now the portfolio on which Ms. Kravets worked with no certain return has suddenly become as timely as it is compelling.

By David W. Dunlap

Modern Times Review

The Feeling of Absence

“The story of five families of political prisoners across Russia through time” is how Olga Kravets’ directing debut It’s Getting Dark introduces itself. But, the film is really about absence. The title suggests completeness, but it is rather the lacking that the film addresses. It draws a line from the past to the present, which exactly conveys the feeling of absence.

Karik Krause’s parents Vera Berseneva and Friedrich Krause, in addition to Taisia Osipova, Ruslan Kutayev, Gennady Kravtsov and Svetlana Davydova are all Russian political prisoners or detainees; the first two of the 1950s USSR and the other three of 21st century Russia. Osipova is active in the opposition party Other Russia, as is her husband; Kutayev organised an ‘illegal’ conference on war deportations in Chechenya during the Sochi Olympics; Kravtsov applied for a job in Sweden; and Davydova phoned the Ukrainian Embassy. This is, apparently, all takes.

Karik Krause’s parents Vera Berseneva and Friedrich Krause, in addition to Taisia Osipova, Ruslan Kutayev, Gennady Kravtsov and Svetlana Davydova are all Russian political prisoners or detainees; the first two of the 1950s USSR and the other three of 21st century Russia. Osipova is active in the opposition party Other Russia, as is her husband; Kutayev organised an ‘illegal’ conference on war deportations in Chechenya during the Sochi Olympics; Kravtsov applied for a job in Sweden; and Davydova phoned the Ukrainian Embassy. This is, apparently, all takes.However, it is not their cases that the film explores or unravels. In fact, we are afforded very limited information about the cases, charges, or court sessions, although the film does catch some information through observed conversations of family members, and presents a few public responses in the press. Contact with foreign authorities and political opposition activities and involvement form some of the reasons for the arrests, though the (false) charges seem more often to involve drugs. The film focuses on the effects of the sentences and the detainment, on the consequences rather than the causes. And these consequences are the absences. Without comments or interviews, It’s Getting Dark shows us family lives interrupted. In the case of Davydova, for instance, we see how her husband trying to run the household while also defending his wife’s case via the phone to the media.

Taisia Osipova was arrested because of her husband’s activities rather than her own, although the official charge was heroin possession.

The filmmakers intertwine observations of the incomplete families with letters read by Karik Krause which address the distance between authors, in this case his parents, and their kids. Krause’s narration is accompanied by shots of apartment buildings seen through window frames, creating the impression of a prison view. The two lines come together when Kravtsov’s wife reads their children a letter from him.

“Unfortunately, it is getting really dark”

Kravets is a documentary photographer, something the careful visual language she and cameraman Nikita Pavlov developed testifies to. Families are mostly filmed in their homes where the absence of loved ones is visible, either explicitly or implicitly. A sense of confinement is accentuated through the images. Texts displaying additional information as well as public responses are projected on top of images, creating a layered visual style.

In the case of Ruslan Kutayev, we move outside and witness how he is taken away, with his young son and family waving goodbye. The women do not seem to take it too seriously. Either the whole situation is utterly incredible, or there is simply nothing to understand because there is nothing. Although the film explicitly condemns the legal practices involved, it is not about blame. The court clerics who are present in Kutayev’s case mention how they are merely doing their jobs – a subtle jab at the higher authorities and an indication that everyone is subjected to their arbitrariness.

At IDFA, Olga Kravets said that people today are sentenced for reposting material on social networks. Returning to Russia in 2012, after a number of years abroad, Kravets found politically motivated arrests in full swing following civic protests. In a bid to underline how this can happen to anyone, she decided to turn away from well-known ‘celebrity’ prisoners and focus on lesser known cases. Things have not improved much since then. “Unfortunately, it is getting really dark”, she added. Kravets now lives in Paris.

By Willemien Sanders

(RU) Открытая Россия

«Здравствуй, Руф! Сегодня арестовали маму…»

Режиссер Ольга Кравец рассказала об истории создания своего фильма «Уже темнеет»

4 декабря на фестивале документального кино «Артдокфест» в Москве состоится показ фильма о российских политзаключенных и их семьях «Уже темнеет». Его автор и режиссер Ольга Кравец — о том, почему она решила снимать такой фильм.

— Как родилась идея фильма?

— В 2012 году когда начали арестовывать людей по «болотному делу». Я подумала, что это начало каких-то более серьезных арестов, скоро будут сажать не только за политическую активность, но доберутся и до просто активных граждан. Мы увидели это на примере Светланы Давыдовой. Я написала синопсис, предложила идею этого фильма одному из западных телеканалов. Они посчитали, что это слишком статично: рассказ о семьях, об их обычной жизни, а зрителям часто нужен экшн, больше динамики. Тогда я решила, что буду сама снимать этот фильм. Я начала работу над ним в 2014 году, а в 2016 закончила.

— Кто герои фильма?

— Кто герои фильма?— Семья Кравцовых (бывший сотрудник ГРУ Геннадий Кравцов осужден за госизмену на 6 лет лишения свободы за то, что в поисках работы послал резюме в Швецию), семья Давыдовых (многодетная мать Светлана Давыдова обвинялась в госизмене, через два месяца ареста была освобождена из под стражи, дело прекращено за отсутствием состава преступления), семья Руслана Кутаева (Руслан Кутаев — известный чеченский общественный деятель; 18 февраля 2014 года в Грозном состоялась научно-практическая конференция «Депортация чеченского народа. Что это было и можно ли это забыть?», которую готовил Кутаев. Конференция не была согласована с властями. 20 февраля его задержали и обвинили в хранении трех граммов героина. Он был приговорен 7 июля 2014 года к 4 годам колонии общего режима), семья Таисии Осиповой (активистка «Другой России» была осуждена на 8 лет колонии за сбыт наркотиков).

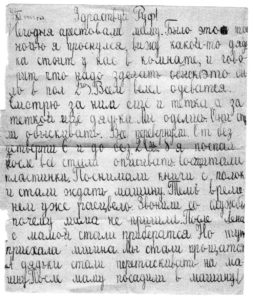

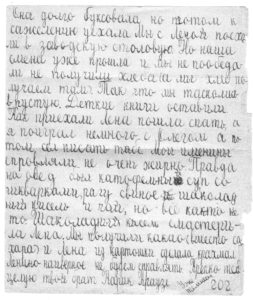

В фильме есть линия из прошлого: Оскар Краузе, сын двух политических заключенных сталинского времени — доктора Фридриха Краузе и его жены Веры Берсеневой. Они оба просидели в сталинском ГУЛАГе: Вера умерла, а он выжил и вышел на свободу. Оскар всю жизнь составлял книгу, в которую вошли письма его родителей из лагеря своим детям. В нашем фильме он читает их. Фильм начинается с его письма, которое он, десятилетний мальчик, отправил своему брату в Москву в тот день, когда арестовали маму. Заканчивается последним письмом, которое Вера прислала сыну из лагеря в 1950 году, незадолго до смерти. Таким образом Оскар связывает рассказанные нами в фильме истории о четырех семьях российских политзаключенных с историей своей семьи.

В фильме есть линия из прошлого: Оскар Краузе, сын двух политических заключенных сталинского времени — доктора Фридриха Краузе и его жены Веры Берсеневой. Они оба просидели в сталинском ГУЛАГе: Вера умерла, а он выжил и вышел на свободу. Оскар всю жизнь составлял книгу, в которую вошли письма его родителей из лагеря своим детям. В нашем фильме он читает их. Фильм начинается с его письма, которое он, десятилетний мальчик, отправил своему брату в Москву в тот день, когда арестовали маму. Заканчивается последним письмом, которое Вера прислала сыну из лагеря в 1950 году, незадолго до смерти. Таким образом Оскар связывает рассказанные нами в фильме истории о четырех семьях российских политзаключенных с историей своей семьи.— Вы показывали фильм на фестивале в Голландии. Как его там приняли?

— Да, фильм пригласили на конкурс в главный фестиваль документального кино IDFA в Европе. Это как Каннский фестиваль для игрового кино, только для документалистов. Для меня была огромная честь представлять фильм на таком фестивале, очень важно было говорить на эту тему перед огромной аудиторией, которая интересуется документальным кино в стране, где у людей развито гражданское сознание. Премии фильм не получил, но его очень тепло приняли. Было четыре показа, на вечерних показах было много людей и все задавали вопросы. На утренний пришло не так много народа, но это было потрясающе, потому что каждый человек, который пришел, очень хотел задать вопрос и получить ответ. Это была самая интересная дискуссия, потому что пришли те, кому все, что происходит в России, реально интересно.

— Какие вопросы задавали зрители?

— Вопросы самые разные. Было много профессионалов кино, которым было интересно узнать, как нам удалось снимать так, что камеру не заметно, что она живет как бы своей жизнью вместе с героями. А обычные люди спрашивали о России Путина, кто-то вспоминал Горбачева, спрашивали, действительно ли можно сравнить сегодняшние колонии с лагерями ГУЛАГа. Я, конечно, предполагала подобные вопросы, потому что с моей стороны было некоей провокацией сравнивать сегодняшние и сталинские лагеря. Я объясняла, что у нас пока не расстреливают. Почему я решила использовать аналогию со сталинскими репрессиями? Когда я только начинала работать над фильмом, я встретилась с одной женщиной, у которой в сталинское время сидели оба родителя. Она мне сказала, что ей кажется, будто бы «история повторяет сама себя». Под впечатлением от этой фразы и появилась в фильме линия советских политзаключенных. Когда меня спрашивают: «Это правда, что сейчас в России все так плохо, как тогда?», я отвечаю: «Нет, действительно, не так. Но для того, чтобы это не стало таким же, как тогда, нам нужно об этом говорить и снимать фильмы».

— Как семья Руслана Кутаева согласилась участвовать в вашем фильме?

— Как семья Руслана Кутаева согласилась участвовать в вашем фильме?— Я езжу в Чечню уже 11 лет. Для меня попасть к Кутаевым было достаточно просто. Меня там многие знают, и я знала Руслана Кутаева до его ареста, потому что он — одна из очень важных фигур для республики и один из немногих интеллектуалов, который из Чечни не уехал. Мне легко было общаться с его семьей.

— А его родственники не боялись, что их участие в вашем фильме может повредить им и Руслану?

— Те люди, которые согласились участвовать в нашем фильме, это люди, которые заранее приняли решение говорить о своих проблемах. Для них возможность бороться с системой — это говорить об этом. Готовясь к съемкам, я встречалась с разными людьми, и 90% из них отказывались участвовать в моем фильме. Они честно признались, что боятся. То есть снявшиеся в фильме люди согласны с моим подходом: если о политических преследованиях говорить и писать, то появляется еще один шанс, что правда о деле того или иного политзаключенного будет услышана, и ситуация изменится в лучшую сторону. Мы видим, что история Светланы Давыдовой — это история освобождения из тюрьмы, которая стала возможна, в частности, благодаря общественному мнению.

— Почему у фильма такое название «Уже темнеет»?

— Это цитата из письма Оскара брату. Он подробно рассказывает об аресте мамы, потом вспоминает о дне рождении сестры и в самом конце пишет: «Крепко тебя целую. Твой брат Карик Краузе. Уже темнеет. СОС».

Письмо Оскара Краузе брату

(Пунктуация и орфография автора сохранены)Здраствуй Руф!

4.11.1942 год

Сегодня арестовали маму. Было это ночью я проснулся, вижу какой-то дядька стоит у нас в комнате и говорит, что надо сделать обыск (это было в полвторого). Всем велел одеваться. Смотрю за ним еще и тетка а за теткой еще дядька. Мы оделись. Они стали обыскивать. Все перевернули. От без четверти 6 и до без двадцати 8. Я поспал после. Все стали описывать. Сосчитали пластинки. Поснимали книги с полок и стали ждать машину. Тем временем уже рассвело. Звонили со службы — почему мама не пришла. После Лена с мамой стали прибираться. Но тут приехала машина. Мы стали прощаться. А дядьки стали перетаскивать на машину. После маму посадили в машину. Она долго буксовала, но потом к сожалению уехала. Мы с Леной поехали в заводскую столовую. Но наша смена уже прошла и мы не пообедали не получили хлеба (а мы хлеб получаем там). Так что мы таскались впустую. Детские книги оставили. Как приехали Лена пошла спать, а я поиграл немного с Олегом а потом сел писать тебе. Мои именины справляли не очень жирно. Правда на обед был картофельный суп со шкварками, рагу свиное шоколадный кисель и чай, но все как-то не то. Шоколадный кисель смастерила Лена. Мы получили какао (вместо сахара) и Лена из картошки сделала крахмал. Ленино наверное не будем справлять. Крепко тебя целую. Твой брат Карик Краузе. Уже темнеет. СОС.Текст Зоя Светова, «Открытая Россия»

Опубликовано 4 Декабря 2016